Current technologies guided by old thought processes can make for a useful combination.

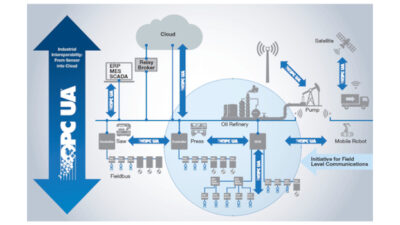

A major part of today’s communication revolves around Ethernet networking. In our world, this is used for either communications or I/O control. The current state-of-the-art network hardware makes the implementation of these types of networks extremely easy and secure. The fact that this is the same technology that is used in every corporation’s IT department makes it even more attractive.

However, because of the fact that it has become commonplace has left it open to that age-old adage “familiarity breeds contempt.” Because of its critical nature, you would expect that industrial networking would be the last area in which lackadaisical planning and implementation is encountered. Sadly that is often not the case.

As engineers, consider the amount of planning that was put forth 15 to 20 years ago in designing your automation communications. Every system manufacturer seemed to have its own topology. Or, when implementing serial communications, numerous environmental conditions impacted performance. Because of this, we planned the networks carefully, adhered to all of the standards and specifications, and provided thorough documentation. Finally, when the networks were installed, they were meticulously tested.

In numerous cases nowadays, I see engineers ignore the lessons of the past and plan for network failure, or certainly problems.

Let’s start with the design and installation documentation. More often than not, the network design is built around a couple of boxes marked “switch” and connecting lines running to other boxes marked “controller.” To make matters worse, periodically the transmission medium will have to change type, from copper to fiber and back, all indicated by that single thin line. If there isn’t a proper drawing, then there will be a spreadsheet of cables to go from “switch” to “field device.” It is then up to the electrical installer to get the routing right.

Be honest, I think we’ve all seen this stuff before.

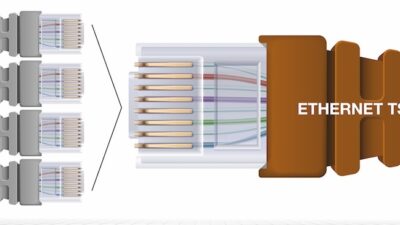

Fundamentally this approach does, at least, convey the barest minimum of information. But consider what happens when it’s time to put the system together. Cable numbers are usually ill-defined if existent at all. This means that the cables have to be rung-out individually. There is also the concern about routing. How protected are the cables from noise and interference? If the cable is fiber optic, that’s not a problem (Although think about mixing multi-mode with single-mode fiber. Yikes!), but copper is not that tolerant when running parallel to VFD cables. After this, there is the concern about cable length. The specification for copper Cat5/5e/6 cable is 100 m (328 ft) device to device. Refer to ANSI/TIA/EIA-568-B.1, 568-B.2, 569-A for details.

Once we’re past the cable runs, we get to terminations. The standards call for field cable termination at a station or patch panel. The primary reason for this is to ensure proper lead separation which reduces crosstalk. A less technical reason, but just as important, is that leads are more reliably landed the first time. Yet I have seen numerous installations just crimp an RJ-45 connector on the cable (leaving more than enough slack of course) and plugging this right into the switch or device. When the cable doesn’t connect, maybe it’s tested for wiring, but generally the ends are cut off and re-terminated. At no point in the above process did we talk about having the cabling, fiber or copper, certified.

Realistically, what needs to happen is what we did in the past: engineer the network for success.

A good place to start for network design is a white paper put out by Cisco and Rockwell Automation titled “Converged Plant-Wide Ethernet Design and Implementation Guide,” which is freely available on the Internet. This covers all aspects of network design and implementation, and is especially useful for secure networking.

Once past the concept, a proper system architecture drawing needs to be created that puts as much thought into the requirements as we used to do as a matter of routine. Nothing can replace proper design and documentation. This also ensures that we’ve accounted for all of the parts and equipment. A properly designed network is very aware of the various media types and their limitations. Multi-mode and single-mode fiber is applied appropriately as well as Cat-6 copper.

From the design, a proper cable and routing schedule can be developed for the installation contractor that has proper cabling numbering. The cables will also be punched down at the patch panels and properly mounted station connectors. This goes a long way to ensure that cabling passes the certification process.

Finally, and most important, all cables will have been tested and certified. A certified network is proof positive that the physical installation meets all of the specifications and is solid. This is the most important part for you as the engineer as well as the customer.

Ultimately, in the end, it is up to us to “sweat the small stuff.”

This post was written by Jeff Monforton. Jeff is a senior engineer at MAVERICK Technologies, a leading system integrator providing industrial automation, operational support, and control systems engineering services in the manufacturing and process industries. MAVERICK delivers expertise and consulting in a wide variety of areas including industrial automation controls, distributed control systems, manufacturing execution systems, operational strategy, and business process optimization. The company provides a full range of automation and controls services – ranging from PID controller tuning and HMI programming to serving as a main automation contractor. Additionally MAVERICK offers industrial and technical staffing services, placing on-site automation, instrumentation and controls engineers.