Humans are the weak link when it comes to cybersecurity and have a wide potential attack surface for hackers, but companies can take steps to reduce this problem by remaining consistent in their security policies. Six personnel shortcomings and three solutions are highlighted.

The term "attack surface" is security jargon for the sum of a company’s security risk exposure. It is the aggregate of all known, unknown, reachable and potentially exploitable weaknesses and vulnerabilities across an organization.

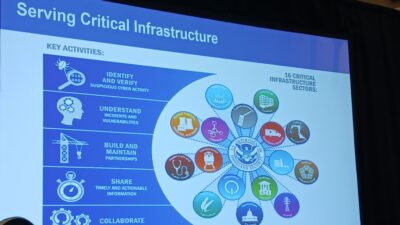

All organizations, regardless of industry, have an attack surface. However, for those who manage energy, utility and other critical infrastructure sites in today’s highly interconnected world, this concept is especially critical to review. Awareness of weaknesses, prioritization of risk and layered defenses can reduce the attack surface and limit disruption, enhance predictable operations and lower business risk.

The attack surface and how to defend it is not a new concept. Broadly oversimplified, the industrial attack surfaces that need defending include (but are not limited to) the following areas:

- Physical and virtualized assets

- Hardware

- Firmware

- Software

- Databases

- Networks (including industrial communications protocols, serial links, remote access, networking devices, firewalls)

- Physical facilities

- Personnel.

The human element of attack surfaces

Out of the list of attack surfaces listed above, one stands out from the rest: Personnel. This is because securing the "human element" is easy to overlook when assessing vulnerable attack surfaces within a network. The human attack surface is the sum of all exploitable security holes or gaps created by humans within an industrial control system (ICS) operations environment. Human behaviors in ICS realms are no different than within many professional settings. As human beings, we make mistakes and are prone to error. However, in ICS and corporate security settings, errors or negligence can have serious physical consequences, even with safety instrumented systems in place.

When considering human factors that can influence the size of the attack surface and, by doing so, putting a business at risk, here are six of the most common personnel shortcomings:

1. Lack of ICS security knowledge. Personnel lacking the appropriate level of ICS security knowledge are more prone to make mistakes. For example, employees or contractors might be charging cell phones or other mobile devices on ICS USB ports, exposing sensitive data belonging to both the company and the employee.

2. Resistance to change (or bypassing security rules/policies to avert disruption). Periodically troubleshooting or "taking care of things" by modifying or updating firmware or asset configurations without letting others know, or doing email on engineering workstations that also have access to HMI consoles are examples of employees knowing the right thing to do but taking the route that causes less friction for themselves and others.

3. Susceptibility to social engineering. Social engineering involves attackers appealing to personnel’s human nature. It’s centered around creating a sense of urgency that pressures people into making risky decisions, or appealing to a person’s innate desire to help others. Social engineering attacks can be as simple as attackers following someone to an employee-only entrance and asking the employee to hold the door because they forgot their ID badge at home.

4. Opportunities for operator error or negligence. As the old saying goes, "To err is human." Personnel are bound to make mistakes from time to time. While some mistakes are easily corrected, some carry serious consequences when put into the context of ICS security. One such example would be sharing the Wi-Fi password for the break room with visiting family members so they can connect personal devices. Managers might also forget to disable network access for former employees and contractors. Both expose the network to a whole host of external threats.

5. Awareness training for email security. Email security protocols should be a top priority. According to the Q2 2017 malware review and research report by email-filtering company Phishme, over 90% of all malware (including ransomware) targets inboxes.

6. Lack of ICS security policies or training. Providing employees with security guidelines and conducting regular training and remediation sessions will keep personnel sharp and alert to security risks. For example, personnel should be aware of both safe and unsafe connections through which they can access plant networks and resources. Logging in at a workstation and jumping on the local Starbucks Wi-Fi are two very different things.

Reducing human attack surface

Companies looking to reduce their human attack surface can focus on three primary areas to make the biggest improvement:

1. Know who has physical and cyber access

The problem: Many people are given access to physical and cyber assets. This is a broader group than just employees. It can include contractors, maintenance and facility workers, industrial equipment manufacturers, system integrators, consultants, supply chain partners, etc. In many cases, the access is supposed to be temporary but never gets revoked.

The solution: Establish and enforce procedures to limit or discontinue physical and cyber access for specific employees and non-employees. This will rightly involve participation of the IT team, human resources and likely those who monitor physical access.

2. Securing email and training personnel

The problem: are among the most common ways to infect systems for a whole array of purposes—from locking users out of their systems to stealing login and password credentials to gaining access to critical assets such as human-machine interfaces (HMIs) or programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and potentially causing disruption or harm.

The solution: Consider acquisition of technology to help filter out suspicious emails and on secure email practices. In a bigger effort, companies should consider a full ICS security program with email security awareness as one of many important components.

3. Social engineering awareness training

The problem: Social engineering has become so common and successful that it deserves its own category of attack surface. Social engineering relies heavily on human interaction and often involves tricking people into breaking normal security procedures, giving up personally identifying information or corporate details.

Popular social engineering techniques rely on a person’s willingness to be helpful or their lack of attention to detail when in a hurry (like not noticing a slightly misspelled URL or website that could indicate malicious intent). These messages often have a tone of urgency that can cause recipients to miss obvious clues. For example, an attacker might pretend to be a co-worker who has some kind of urgent problem that requires access to additional network resources.

There are many variants of social engineering that also involve social media such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn and even text messages sent via cell phones. After research and possibly a few phone calls, social engineers could craft effective spear phishing emails, causing C-suite, privileged users and field technicians to fall prey.

The solution: Reducing the social engineering attack surface will require educating employees about typical techniques and how to recognize them. This facet of the human attack surface is constantly changing and will require monitoring for trends that may apply to any industry, locale, or employee type. This information can help employees recognize interactions that could lead to compromise, disruption, and operations downtime.

One of the great strengths of highly secure organizations is their emphasis on communicating security awareness, cyber-physical risks and safety principles to their employees, partners, supply chain and even their customers (as when using the web to gain secure access to pay their utility bill.)

Jeff Lund, senior director, product line management, Belden. This article originally appeared on the Industrial Internet Consortium’s (IIC’s) blog. Edited by Chris Vavra, production editor, Control Engineering, CFE Media, [email protected].