For years, software vendors have waged a war of words over which class of applications should be deemed the "backbone" system for manufacturing enterprises. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) vendors were the first to lay claim to this title, and for good reason. They were the first to bring any real level of software-based automation to the manufacturing realm.

For years, software vendors have waged a war of words over which class of applications should be deemed the "backbone" system for manufacturing enterprises.

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) vendors were the first to lay claim to this title, and for good reason. They were the first to bring any real level of software-based automation to the manufacturing realm.

Before long, however, supply chain management vendors—with their fancy algorithms for creating the "optimal" schedules for building and delivering parts—declared ERP obsolete. During the height of the Internet boom, one supply chain vendor boasted that its system would not only become the backbone of the manufacturing enterprise; it also would be the engine behind Web sites on which consumers could place orders for custom-configured products and thereby trigger the chain of events required to have those products built and delivered on the exact dates customers requested.

That hasn’t happened yet, and supply chain management systems, for the most part, have been absorbed into ERP platforms. Still, the fight for the title of enterprise backbone continues, with product lifecycle management (PLM) software vendors now laying claim to the designation.

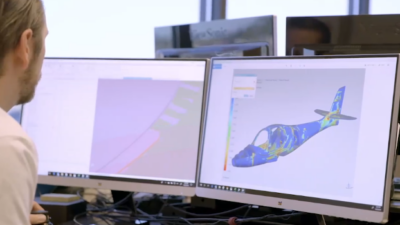

Past experience has caused me to avoid discussions about enterprise backbones. But I do know that recent developments in the PLM space—specifically the emergence of geometrically accurate 3D models and simulation applications—have greatly enhanced the value of this class of software.

I got a sense of just how valuable these tools can be when I chatted with John Mahoney, leader of the Innovation Group, at Entergy Nuclear, at the recent Dassault Systemes user conference.

Entergy is modernizing the 11 nuclear power plants it operates across the U.S. In the process of replacing a reactor cooling pump, Entergy engineers discovered they didn’t have complete drawings of the pump and the containment area in which it was located. That meant they weren’t quite sure of the best way of removing the pump.

To resolve that problem, Entergy employed laser scanning equipment to take a picture of the pump and its surroundings.

Data from the scan was loaded into Dassault’s CATIA CAD program, where a 3D model was generated. The model revealed that two pieces of equipment—which didn’t show up Entergry’s paper drawings—would not allow for removing the pump in the way the engineers originally had planned.

Using Dassault’s DELMIA manufacturing process management software to simulate removing the pump, Entergy engineers discovered that if they rotated it in a certain fashion they could pull it out of the containment area without hitting any obstructions.

Without that simulation, Mahoney said, Entergy would have sent engineers into the area to figure out a removal method, and they might not have come up with what proved to be a fairly simple solution.

"Most likely we would have had to shut down the plant to remove the pump, which would have cost $1 million a day, and we would have had to subject some of our people to a radiation dose," he said.

Removing nuclear reactor cooling pumps is not the same as making products, but uncovering potential obstacles—and figuring out the most cost-effective way of avoiding them—is a good idea in any line of business.