Automation system integrators are experts at planning, designing, and implementing industrial automation and control systems. They're particularly adept at connecting disparate automation components to equipment in a client's factory. Exactly how they accomplish their mission varies from integrator to integrator and from application to application.

At a Glance

Phases of a typical automation project

Issues to address

Pitfalls to avoid

Sidebars: Tips for starting an automation project on the right foot

Tips for managing the project

Automation system integrators are experts at planning, designing, and implementing industrial automation and control systems. They’re particularly adept at connecting disparate automation components to equipment in a client’s factory.

Exactly how they accomplish their mission varies from integrator to integrator and from application to application. There are as many methods for executing automation projects as there are engineers who work on them. However, certain elements of the development process are critical to the success of any project.

Getting started

From the system integrator’s perspective, the process generally begins when the client first calls with an idea. Various meetings, phone calls, and documents will typically ensue to further clarify the client’s needs and ascertain whether or not the proposed project is feasible.

“A pre-kickoff requirements gathering phase—when project managers can discover and document who the project stakeholders are, what they expect from the project, and why they have those expectations—is critical to the long-term success of the project,” says Jeffrey Knox, director of business development for The ESCO Group. See “Tips for Starting an Automation Project on the Right Foot” for specific steps he suggests for this phase of the project.

Requesting a proposal

This brainstorming will typically lead to a formal request for proposal (RFP) outlining the client’s objectives and goals for the project, the scope of work the client will expect the integrator to undertake, and some of the basic commercial issues, such as payments and deliverables. The RFP need not specify every detail about how the proposed control system should be implemented, but it should accurately reflect the desired look and feel of the final product.

A well-considered RFP can prevent unwelcome surprises down the road. According to Robert Zeigenfuse, president of Advanced Automation Associates, “Without this upfront agreement, specifications will be approved, design will be initiated, and software will then be written—despite the fact that the content of the specifications will probably not have been understood, possibly not even known, by all of the involved parties.”

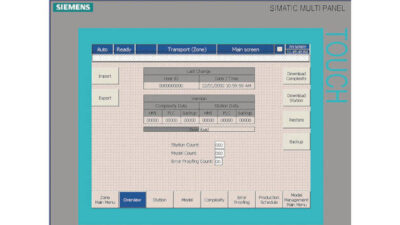

Instead, he suggests that the client devise a prototype of the control system as it would appear on the operators’ terminals, including all of the details that would be shown on each screen once the system is operational. “No actual code is contained behind the controls since this is premature at this stage. Each screen is reviewed with the client along with a discussion of the functionality behind every object on the screen.”

Planning a strategy

Once all parties understand what is to be done, the integrator can propose a strategy and a budget for making it happen. In this and subsequent design documents, a detailed plan for executing the project takes shape.

The degree of detail required for the project plan varies with the application. Installation of a single PLC may require no more than an outline of the functions that the PLC is to perform, the corresponding assignments to be completed by each of the engineers involved, and a timetable for the completion of each step.

For a plant-wide automation system, however, the project plan may occupy several volumes and specify the non-technical details for each of several phases of the project. It can include reporting procedures, organizational charts, contingency plans (to cover unforeseen events, such as equipment shortages or natural disasters), alternative implementation strategies, approved vendor lists, and specifications on each party’s financial responsibilities.

Designing a solution

With the project plan in place, the engineers can begin to flesh out the technical details. RBB Systems has codified its procedures for this stage of the project with the flowchart shown in “Translating Technical Requirements into a Design.”

A particularly complicated project may require an initial set of preliminary designs to show how the completed automation system will actually work and how it will accomplish the objectives outlined in the project plan. Ideally, the engineers who will ultimately be responsible for implementing it—the client’s engineers, the integrator’s staff, or both—should generate the preliminary design.

The preliminary design need not include every detail about wiring connections, program code, hardware placement, etc. Those specifics can be deferred to a later round of detailed designs. Preliminary design should show roughly how the project plan is to be implemented. Detailed design then fills in the particulars. It is not particularly important to decide which design elements belong in each document so long as the entire project is completely described and well understood by all parties when the design is complete.

Implementing the project

If the design documents are thorough, the implementation phase becomes a matter of following the design’s recipe for assembling the system components. There is a tendency, however, to start implementation as soon as the equipment becomes available, even if the design isn’t quite finished. After all, running wires and banging out computer code seems more productive than churning out more paperwork.

Unfortunately, attempting hardware installation before the design is cast in concrete can cause more trouble than it’s worth. A rack of two-channel analog input modules may have to be replaced with a rack of four-channel modules if additional sensors are added later in the design process. A thermocouple may have to be replaced with an RTD if it is decided that a particular temperature measurement requires greater accuracy. Even seemingly simple changes that are easily rendered on paper can be difficult to implement once the hardware is in place.

Details of the implementation phase vary from application to application. Perhaps the only common factors that all automation projects share are the ever-present deadlines. Deadlines for reaching specific milestones are generally specified in the project plan to make sure that the project continues to move forward.

Missing or “slipping” a deadline is not uncommon, since the full scope of the project may not be evident early on when the project plan is being developed. A realistic project plan will schedule extra time for unexpected delays and for tasks that prove to be more time-consuming than originally anticipated. Any slippage beyond that margin generally results in a financial penalty for the integrator, though early completion can also be rewarded with a bonus.

Communicating along the way

All this proposing, planning, designing, and implementing works best when everyone involved knows what everyone else is doing. In fact, says Alan Kelm, a senior project manager for Bay-Tec Engineering, “the personal touch— face-to-face meetings and open communications they encourage—can be the most important aspect in the project management life-cycle methodology.”

Kelm suggests scheduling three kinds of meetings during the course of the project. Meetings with the client are particularly important during the design phase. According to Kelm, “It is imperative to keep the customer involved to ensure that there are no discrepancies between what the customer understands the design to be and what the design ends up being.”

For the integrator’s own staff, turnover meetings should be held whenever one project phase is complete and another begins. This allows passing project information from one department to another. These would include turnovers from sales to project management after the proposal has been accepted, engineering to fabrication after the hardware designs have been completed, and engineering to field installation after all the in-house assembly has been completed.

Weekly project team meetings allow different departments to interact, evaluate schedules, and address problems. These meetings allow the project manager to assess the project’s current status by determining what project milestones have been achieved, what milestones are upcoming, and what manpower adjustments are required to stay on schedule.

Signing off

When the project is eventually completed, it’s time to determine if the client actually got what he asked for. Acceptance tests are conducted to assess the performance of the automation system—in-house, where the components were assembled, as well as in the factory with the assembled components installed and operational.

Questions to be answered by the acceptance test should already be delineated in the project plan. Unless all parties agree up front on how to determine when the required work has been completed and if it has been done correctly, the project will never end. The client would probably prefer to have the integrator’s engineers on call, making improvements for the rest of the system’s lifetime; but the engineers must be able to stop working on the project at some point.

All that remains once the acceptance tests are complete is the final sign-off. That sounds easy, but it can be difficult to get all parties involved to sign a document stating that the project in its current condition is as complete as it’s going to get. Even the engineers who should be looking towards their next assignments are often tempted to make “one last adjustment” before calling it quits.

Unfortunately, there never is just one last adjustment to be made. Fine tuning the system’s performance is an ongoing effort that can last throughout the system’s lifetime. A well-designed automation system will include provisions for future changes, preferably changes that the client’s engineers can make.

Remaining flexible

The steps outlined above are by no means fixed and immutable. The order of execution can be varied to fit the project, and some steps can be left out entirely. A single design document is often sufficient for a smaller project, for example.

Perhaps the most common deviation from this sequence occurs when a client changes his mind. Unforeseen budget constraints handed down after the project plan is approved may require postponing or eliminating certain elements of the project. Plant personnel may realize during the implementation phase that another element must be worked into the design to make the rest of the system work. For whatever reason, there are almost always occasions when the project must be moved backward through the execution order rather than forward. No plan is perfect.

Tips for starting an automation project on the right foot

Determine the business purpose of the project.How will the project create a return on investment or provide the stakeholders with information needed to make sound business decisions?

Determine the system requirements of each stakeholder during and after the project.Who will be affected by this project? Why do they want to see it completed and how do they think it will affect their jobs?

Determine project constraints.What resources will be available in terms of money, time, technology, and talent?

Organize, present, and gain approval from stakeholders.Will all of the requirements set forth by the stakeholders be met by the project as planned? Can the requirements be met within the project’s constraints?

Track requirement completion and satisfaction of the stakeholders.Are the agreed upon requirements being met?

Source: The ESCO Group

Tips for managing the project

The Control and Information System Integrators Association (CSIA) has published some tips to ensure automation projects are executed and managed consistently. CSIA’s “Best Practices and Benchmarks Manual and Guide to Selecting and Working with a Control Systems Integrator” asks key questions that clients ought to raise with their system integrators during the early stages of the planning phase. For example:

Does the integrator assign personnel to a project team who are experienced and qualified in the area required?

Are the assigned personnel’s time commitments considered in assigning a project?

Does the integrator require that key project staff be properly briefed on overall scope?

Does the integrator review the project plan to ensure client expectations are understood? Are project plans presented to the client for approval?

Does the integrator have a formal process for releasing a project from sales to operations?

Suggested answers are included along with a variety of planning tips that can be customized to a wide variety of projects. For copies of these references, contact the CSIA’s Executive Director Norm O’Leary [email protected]